As my classes this year begin to wind down, I find myself making frequent glances in the rearview mirror, looking back at all the worlds I have led my students through. From the electric streetlights of New York to the vast acreage of the Russian countryside, from the courts of Denmark to the Paris Opera House, the wintry streets of Victorian London to the cramped apartment of a desperate salesman*, I am taken aback by the sheer beauty and splendor afforded in the simple pleasure of reading books.

As my classes this year begin to wind down, I find myself making frequent glances in the rearview mirror, looking back at all the worlds I have led my students through. From the electric streetlights of New York to the vast acreage of the Russian countryside, from the courts of Denmark to the Paris Opera House, the wintry streets of Victorian London to the cramped apartment of a desperate salesman*, I am taken aback by the sheer beauty and splendor afforded in the simple pleasure of reading books.

One particular glory, and perhaps the preeminent one, is the power stories have to speak the truth. As someone once said, fiction is “the lie that tells the truth,” and so, I’d like to share three classic works of fiction that, I contend, edify and encourage the believer through their depiction of the Great Story that God is telling. These are simply a small handful of works that reveal, in some measure, either in their portrayal of man’s tragedy or his redemption, the awesome wonder of the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

- Silas Marner by George Eliot

Falsely accused and abandoned by both his fiancee and his best friend, the weaver Silas Marner’s most grievous despair comes from the loss of his faith in the process. God, it would seem, has also withdrawn, leaving him desperate and alone in a home that has lost all familiarity, all comfort. So Silas retreats from his beloved old life and further into the darkened caverns of his battered heart.

Yet, in true form, all is not lost, for God, the beloved Father, has never left Silas Marner’s side. As the weaver burrows himself deeper in his gloom, God sends a wandering, helpless child through his door, toddling her way to the warm fire. As the novel progresses, Silas must learn to father little Eppie and raise her to love and care in a world lacking such virtues. A beautiful work of loss and redemption, sadness and joy, Silas Marner shows us the goodness of a sovereign God who designs all things, both sorrow and gladness, to His fullest glory.

2. Great Expectations by Charles Dickens

Pip, the poor orphan boy raised “by hand” by an abusive sister, lives on the scraps and meager margins of life. Opening the novel alone in his parents’ graveyard, Pip suddenly finds himself on the receiving end of death threats from a hardened, terrifying convict, demanding food and a file to free his chains. Yet, though Pip has nothing of a future ahead of him, he dreams of a life in London, the top hats and cobblestone streets, the theater and the busy coaches. In short, Pip dreams of being a somebody. And so, when a mysterious benefactor sends him an inexplicably magnificent fortune, granting Pip the impossible opportunity to attain his expectations, Pip is ecstatic.

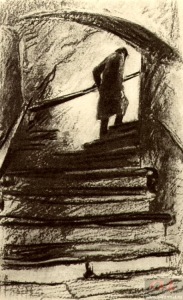

But, as Pip finds, not all that glitters is gold. Throughout Pip’s experience in the city, he must, both literally and figuratively, wave the fog and chimney mist from his eyes, constantly wiping away the crumbling illusions of his makeshift fantasies. The world, Pip discovers, is greedier, crueler, dirtier, and lonelier than he had imagined. What remains for Pip, then, is to watch his worldly ambitions fade to nothing only to discover the true joy and grace that had been beckoning to him all along. Considered by many to be Dickens’ masterpiece, Great Expectations guides its reader from the warmth of home to the prodigal “far country” and, thankfully, back again with the spiritual richness and stylistic aplomb typical of Dickensian fiction.

3. Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

At once both Gothic thriller and philosophical discourse, Frankenstein perhaps is one of the more misrepresented works of Romantic literature. Dr. Victor Frankenstein is obsessed with scientific exploration and daring feats of progress, namely, the discovery of reanimation and the source of life. Written in the short wake of Galvani’s work with electricity, Shelley’s novel examines the ethical, social, and religious implications of playing God as Frankenstein assembles a motley cadaver from dead men’s limbs and surges it to life. Yet, the creature he thought would bring him worldwide renown and adoration in the scientific community turns out to be a harrowing monster, eight feet tall and more powerful than Frankenstein had ever dreamed. What follows is a cat-and-mouse pursuit as Frankenstein runs from his creature and, ultimately, the consequences of his deeds.

The true beauty of this novel, however, lies in the way Shelley provokes sympathy for the monster. In her world, this creature becomes a being that longs to know its telos, its purpose, in this hostile and chaotic world. The monster, in this sense, is transformed into a type of Adam, created and designed by an expert hand, as he subsequently roams western Europe in search of his maker. Perhaps the most climactic and stirring moment occurs when Frankenstein and his monster meet atop Mount Blanc, embodying the classic , almost mythical confrontation between creature and creator. In this sequence, the monster finally interrogates Frankenstein, begging him to accept him, love him, and explain his purpose for being. Yet, for all his earnest pleading, the monster receives no kindness in turn as Frankenstein berates and abandons him, damning him to his alienated and miserable state alone and confused.

As awful as Frankenstein treats his creature, the story awakens the reader’s heart to the contrary opportunity we all have in addressing our own Maker. Unlike Frankenstein, He will never spurn us with disgust; rather, we serve a good Father who made us in His living image, not from the rotted, corroding skin of death. In this way, Frankenstein shows us the inadequacy of humanism compared to the lovingkindness of a sovereign God. We, as it turns out, make lousy gods.

*These works are The Great Gatsby, The Seagull, Hamlet, The Phantom of the Opera, Great Expectations, and The Metamorphosis.

This list is unbearably narrow, meaning that the work of contemporaries like Matthew Arnold, Charles Spurgeon, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Alfred Tennyson, and Abraham Lincoln are criminally unmentioned.

This list is unbearably narrow, meaning that the work of contemporaries like Matthew Arnold, Charles Spurgeon, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Alfred Tennyson, and Abraham Lincoln are criminally unmentioned.

On a lighter note (…possibly, depending on your interpretation), Lewis Carroll publishes his famous work Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in 1865, and readers everywhere have been led down the rabbit hole ever since.

On a lighter note (…possibly, depending on your interpretation), Lewis Carroll publishes his famous work Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in 1865, and readers everywhere have been led down the rabbit hole ever since. I am working my way through Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment and was struck by one of its early scenes depicting a drunkard in a St. Petersburg tavern bemoaning his vices, as well as the costs they have accumulated, to the novel’s protagonist Rodya Raskolnikov.

I am working my way through Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment and was struck by one of its early scenes depicting a drunkard in a St. Petersburg tavern bemoaning his vices, as well as the costs they have accumulated, to the novel’s protagonist Rodya Raskolnikov. At the end of Les Misérables, as Jean Valjean lies dying before his beloved daughter Cosette and her husband-to-be Marius, the musical swells to a beautiful arrangement of different musical themes sung by Valjean, a vision of Fantine, and reprising his earlier role, the Bishop of Digne. In this stirring scene, Valjean commends Marius and Cosette to marry and reveals his long-held secret that he, in fact, is prisoner #24601, tired from a life of running from the law. As Valjean sings his last confession, Fantine appears to welcome him into heaven, accompanying his reflection on the grace he has been shown and his attempt to live a life worthy of it. At last, Valjean sees the Bishop, the noble priest who initiated the entirety of Valjean’s redemption by welcoming him to his home, forgiving his crime, and graciously setting him free, transforming him into a new man whose soul has been “bought for God”. Notice the kindness and sacrificial love of the priest as he gives Valjean the candlesticks at the beginning of the musical:

At the end of Les Misérables, as Jean Valjean lies dying before his beloved daughter Cosette and her husband-to-be Marius, the musical swells to a beautiful arrangement of different musical themes sung by Valjean, a vision of Fantine, and reprising his earlier role, the Bishop of Digne. In this stirring scene, Valjean commends Marius and Cosette to marry and reveals his long-held secret that he, in fact, is prisoner #24601, tired from a life of running from the law. As Valjean sings his last confession, Fantine appears to welcome him into heaven, accompanying his reflection on the grace he has been shown and his attempt to live a life worthy of it. At last, Valjean sees the Bishop, the noble priest who initiated the entirety of Valjean’s redemption by welcoming him to his home, forgiving his crime, and graciously setting him free, transforming him into a new man whose soul has been “bought for God”. Notice the kindness and sacrificial love of the priest as he gives Valjean the candlesticks at the beginning of the musical: No statement better captures the spiritual center of the story as Valjean fully takes the measure of how strong grace truly is. One simple act of kindness, unmerited yet fully proffered, has the power to transform a filthy sinner into a forgiven saint. Even in his humble and lowly position, the priest became a vessel for Valjean and, by extension, the audience to see the very face of God through his indefinable love for an embittered thief.

No statement better captures the spiritual center of the story as Valjean fully takes the measure of how strong grace truly is. One simple act of kindness, unmerited yet fully proffered, has the power to transform a filthy sinner into a forgiven saint. Even in his humble and lowly position, the priest became a vessel for Valjean and, by extension, the audience to see the very face of God through his indefinable love for an embittered thief. Yes, you must forgive me for making another plug for the poetry of Billy Collins. But seeing as today marks the one-year anniversary of launching Eden.Babel, I find myself musing,

Yes, you must forgive me for making another plug for the poetry of Billy Collins. But seeing as today marks the one-year anniversary of launching Eden.Babel, I find myself musing,

It is often said that in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king. Yet, what must be said of the two-eyed man?

It is often said that in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king. Yet, what must be said of the two-eyed man? As my classes this year begin to wind down, I find myself making frequent glances in the rearview mirror, looking back at all the worlds I have led my students through. From the electric streetlights of New York to the vast acreage of the Russian countryside, from the courts of Denmark to the Paris Opera House, the wintry streets of Victorian London to the cramped apartment of a desperate salesman*, I am taken aback by the sheer beauty and splendor afforded in the simple pleasure of reading books.

As my classes this year begin to wind down, I find myself making frequent glances in the rearview mirror, looking back at all the worlds I have led my students through. From the electric streetlights of New York to the vast acreage of the Russian countryside, from the courts of Denmark to the Paris Opera House, the wintry streets of Victorian London to the cramped apartment of a desperate salesman*, I am taken aback by the sheer beauty and splendor afforded in the simple pleasure of reading books. In Charles Dickens’ near-perfect novella A Christmas Carol, the iconic miser Ebenezer Scrooge endures a painful series of journeys to the past, present, and future to discover the depths of his selfishness and to redeem his crooked heart. Among his famous visits to Mr. Fezziwig’s party, the Cratchit house, and his own grave, one scene in particular is quite moving. As the Ghost of Christmas Past reveals to Scrooge a number of scenes of his boyhood and younger years, a vision of his potential, yet ultimately unrealized marriage to Belle appears, causing Scrooge to beg the Ghost to “show [him] no more!” In this episode, Belle pleads with the younger Scrooge to remember his former love and affection toward her, feelings which had grown cold over time as his piles of gold rose ever higher:

In Charles Dickens’ near-perfect novella A Christmas Carol, the iconic miser Ebenezer Scrooge endures a painful series of journeys to the past, present, and future to discover the depths of his selfishness and to redeem his crooked heart. Among his famous visits to Mr. Fezziwig’s party, the Cratchit house, and his own grave, one scene in particular is quite moving. As the Ghost of Christmas Past reveals to Scrooge a number of scenes of his boyhood and younger years, a vision of his potential, yet ultimately unrealized marriage to Belle appears, causing Scrooge to beg the Ghost to “show [him] no more!” In this episode, Belle pleads with the younger Scrooge to remember his former love and affection toward her, feelings which had grown cold over time as his piles of gold rose ever higher: