…in which I discuss my poem “Yard Sale” from The Cardinal Turns the Corner.

As the night centered itself behind a thousand stars,

Your voice cut the cables in my mind,

And I fell to the corner of 8th street,

Where I found my shadow in some shallow gravel water,

My pupils exhaling,

Unwinding,

Widening to devour my vision –

Dilated thick like dark ink.

The sharp steel of your footsteps raked like teeth to a stop,

Surrounded by the blur of city light

As I knelt alone, rooked in the corner, undone and

Enveloped in the venom of my name

On your silver tongue.

The earth stammered when you spoke, quivering beneath

The bass of your breathing lies

As you slowly taught me how to drown.

And now I see

How your every word howls,

Choking and decoding my defenses,

Coursing through my chemistry,

Anchoring the fever to my bones until they shiver

Like sparrows in the cold.

And when you lean in closer

To tear apart the helix,

My knuckles rust, robotic,

Helpless to your redirection,

Heavy with the burden of entanglement –

Short circuits and crossed wires –

Reprogrammed to believe in you

And all your bitter charming.

So I time a desperate prayer to touch

The crest of tossing waves,

To clear the fog and wind within

And find my loving Father,

Tell Him that I’m sorry,

Then beg He take a shovel to this serpent on the corner,

Calm my frightened eyes and

Pull the poison from my spine

That I might stand up straight

And finally become human again.

I am working my way through Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment and was struck by one of its early scenes depicting a drunkard in a St. Petersburg tavern bemoaning his vices, as well as the costs they have accumulated, to the novel’s protagonist Rodya Raskolnikov.

I am working my way through Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment and was struck by one of its early scenes depicting a drunkard in a St. Petersburg tavern bemoaning his vices, as well as the costs they have accumulated, to the novel’s protagonist Rodya Raskolnikov.

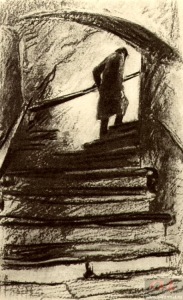

To set the scene, Marmeladov is a sickly alcoholic who has drowned himself beyond the breaking point in his sins. With each vain attempt at repentance, Marmeladov, like a dog to his vomit, returns again and again to his excesses, much to the despair and fury of his long-suffering wife and children. In fact, Marmeladov mumbles to Raskolnikov that his drinking has even pushed his daughter Sonya into prostitution to keep the family above water while he lurches night after night down the old steps into the dingy bar.

In his extensive monologue, Marmeladov admits his depravity and the egregious consequences it is creating, yet he feels compelled to linger in his darkness, a tension that pits sin and redemption on opposite ends of the same locked door of the heart, thus foreshadowing Raskolnikov’s own division as he crouches behind the door of the old pawnbroker moments before her murder.

By the end of his rambling speech, however, Marmeladov rises to a momentous occasion in which he declares he “ought to be crucified” and judged rightly for his wickedness. He even tells the bartender: “Do you suppose, you that sell, that this pint of yours has been sweet to me? It was tribulation I sought at the bottom of it, tears and tribulation, and I have found it, and I have tasted it.” Here, Marmeladov has reached the nadir of his troubles and has realized his inability to see joy, redemption, or hope in his bottomless search; neither in beer nor the tears it draws can salvation be found.

At the climax of his speech, Marmeladov looks forward to the final judgment of Christ in which all will be exposed and all will be made right. Read the beauty of his plea:

“And He will say, ‘Come to me! I have already forgiven thee once…Thy sins which are many are forgiven thee for thou hast loved much’ […] And when He has done with all of them, then He will summon us. ‘You too come forth,’ He will say, ‘Come forth ye drunkards, come forth, ye weak ones, come forth, ye children of shame!’ […] And the wise ones and those of understanding will say, ‘Oh Lord, why dost Thou receive these men?’ And He will say, ‘This is why I receive them, oh ye wise, this is why I receive them, oh ye of understanding, that not one of them believed himself to be worthy of this.'”

Few moments in literature parallel with this piercing declaration of hope in the face of hollow living. Marmeladov, for all his sinfulness and despair, preaches the gospel in a dim-lit corner of a Russian pub. He has vainly sought peace in his drink and in his darkness, yet he discovers that it is in such darkness that illumination may rise. The voice of Christ beckoning all who are weary, all who are broken, all who are drunken to rise, like Lazarus, and come forth into the light is one of the most beautiful pictures Dostoevsky imagines, and he seats it right in the opening of a harrowing novel full of shadow and fear. It is perhaps no wonder his original title for the book was The Drunkards, for that is what every character, in his soul, is. And since Hamlet was right in declaring all art to “hold a mirror up to nature” and expose our own innermost realities, we as readers instantly recognize our own spiritual drunkenness, our own Marmeladovian depravity. Therefore, as Raskolnikov begins his own plummeting spiral over the rest of the novel, we too are caught in the plunge, equally complicit in the powers of darkness that await the resurrecting call of Christ. We too are drunkards, and our only salvation will come from the belief that we are unworthy of it.

Like Jean Valjean’s defining moment of forgiveness from the bishop in Les Miserables, Marmeladov faces the depths of his own sin in the light of Christ’s glory and grace. It is not in the rack of guilt or the metallic strictness of the law that such men hear God but in the beautiful touch of pity and grace. Like Valjean, Marmeladov sees, though ethereally, the mercy of God extended even to him, and struck to the bone, he seeks the light of redemption. Like Valjean, he is brought to a full understanding of his wickedness, and there, only there, may he see the extended hand of God lifting him up. And so in reading such masterpieces, may we also be brought to the pits of our own sin, may we also see our offenses for what they are, so that we may be forgiven, shown grace, and restored to our full humanity. May we drunkards hear the call to quit the shadows and ascend from the grave into the marvelous light of God.

At the end of Les Misérables, as Jean Valjean lies dying before his beloved daughter Cosette and her husband-to-be Marius, the musical swells to a beautiful arrangement of different musical themes sung by Valjean, a vision of Fantine, and reprising his earlier role, the Bishop of Digne. In this stirring scene, Valjean commends Marius and Cosette to marry and reveals his long-held secret that he, in fact, is prisoner #24601, tired from a life of running from the law. As Valjean sings his last confession, Fantine appears to welcome him into heaven, accompanying his reflection on the grace he has been shown and his attempt to live a life worthy of it. At last, Valjean sees the Bishop, the noble priest who initiated the entirety of Valjean’s redemption by welcoming him to his home, forgiving his crime, and graciously setting him free, transforming him into a new man whose soul has been “bought for God”. Notice the kindness and sacrificial love of the priest as he gives Valjean the candlesticks at the beginning of the musical:

At the end of Les Misérables, as Jean Valjean lies dying before his beloved daughter Cosette and her husband-to-be Marius, the musical swells to a beautiful arrangement of different musical themes sung by Valjean, a vision of Fantine, and reprising his earlier role, the Bishop of Digne. In this stirring scene, Valjean commends Marius and Cosette to marry and reveals his long-held secret that he, in fact, is prisoner #24601, tired from a life of running from the law. As Valjean sings his last confession, Fantine appears to welcome him into heaven, accompanying his reflection on the grace he has been shown and his attempt to live a life worthy of it. At last, Valjean sees the Bishop, the noble priest who initiated the entirety of Valjean’s redemption by welcoming him to his home, forgiving his crime, and graciously setting him free, transforming him into a new man whose soul has been “bought for God”. Notice the kindness and sacrificial love of the priest as he gives Valjean the candlesticks at the beginning of the musical:

“But my friend you left so early / Surely something slipped your mind / You forgot I gave these also / Would you leave the best behind?”

Here, in Valjean’s final hour, he experiences an almost beatific vision of the priest, surrounded gloriously in candlelight in the 2012 film adaptation, as they sing one of the show’s most gorgeous lines:

“To love another person is to see the face of God”

No statement better captures the spiritual center of the story as Valjean fully takes the measure of how strong grace truly is. One simple act of kindness, unmerited yet fully proffered, has the power to transform a filthy sinner into a forgiven saint. Even in his humble and lowly position, the priest became a vessel for Valjean and, by extension, the audience to see the very face of God through his indefinable love for an embittered thief.

No statement better captures the spiritual center of the story as Valjean fully takes the measure of how strong grace truly is. One simple act of kindness, unmerited yet fully proffered, has the power to transform a filthy sinner into a forgiven saint. Even in his humble and lowly position, the priest became a vessel for Valjean and, by extension, the audience to see the very face of God through his indefinable love for an embittered thief.

For such wild forgiveness and abundant grace effuses from our Father, the Almighty God who turns slaves into sons and frees us all from the burdens of our many years in prison. Like the Bishop, God offers rest for the weary, comfort for the resentful, love for the unloving and unlovely. Like the Bishop, God transforms the nameless prisoner (24601) into a new man, restored to life, saved not by good works but to them, called to let the grace with which he’s been filled spill over to another. When Valjean is forgiven, he is free to shed his old life and commit himself to a life of service, redeeming little Cosette from her equally dismal life.

In I John 3:16, the apostle describes this love of the Father: “By this we know love, that he laid down his life for us, and we ought to lay down our lives for the brothers” This selflessness characterizes love and, as God is love, draws us closer to His nature. Since we are called to imitate God (Eph. 5:1), learning to love others as He is love is the way forward.

In Romans, “Owe no one anything, except to love each other, for the one who loves another has fulfilled the law.” Incidentally, this truth explains Javert’s ultimate self-destruction. No man so bound to the duties of the law can function, for the law is fulfilled in love; the only way Christ could fulfill the law is in his final breath dying for His friends. As Javert’s inability to cope with such love and grace becomes his undoing, Valjean’s embrace of it in giving his life to Cosette, Marius, and the dozens of young boys at the barricades becomes his way to salvation.

“Above all, keep loving one another earnestly, since love covers a multitude of sins. Show hospitality to one another without grumbling . As each has received a gift, use it to serve one another, as good stewards of God’s varied grace” (I Peter 4:8-10).

Over the past few weeks, I have seen an old foe rise from the troubled waters and beckon me back to an ancient struggle.

The fear of inadequacy.

For as long as I can remember, I have felt the ache to be enough, to measure up to some impossible standard, to gain some infinite approval. I grew up sandwiched in the middle of an unbelievably remarkable family, and, as a result, I have often tasted the lie that I must do an endless number of things to meet the wave of expectations that, like a tide, arrive just as quickly as the former one falls. I felt that to be something, I must do everything.

So, I conditioned myself to chase excellence at all costs, to show my father, mother, sister, brothers, teachers, friends, and God that I mattered. And I exhausted myself in the process. So consumed was I by this pattern of thought that, were I whisked away to heaven, the first words to tumble out of my mouth upon seeing the Father face to face would be:

“Are you proud of me? Did I do well?”

Well, all this to say, I would like to introduce my guest writer for this post. Julie Blanton is a previous student of mine; she is a brilliant writer and a passionate follower of Jesus. I asked her some weeks ago if she’d be willing to write something for Eden.Babel, and I was floored by what she sent me. May you be as blessed and encouraged by this post as I was as we all seek to experience the full mercy and grace of our loving, welcoming, kissing, embracing, dancing, rejoicing Father.

I was raised in a Christian home. I went to a Christian school from the ages of five to eighteen. Church on Sundays was very familiar to me and was never something to be missed. I am so blessed to have been raised in such a loving, Christ-centered family.

I was raised in a Christian home. I went to a Christian school from the ages of five to eighteen. Church on Sundays was very familiar to me and was never something to be missed. I am so blessed to have been raised in such a loving, Christ-centered family.

But, at 15, while I was going to youth group, while I was going to a great church every Sunday and while I had the freedom to pray to God any hour of the day, I was still missing something.

On the outside, I was living a typical Christian American life. I fit into the mold. Yet, although I went to church on Sundays, tried my best to be a “good person”, followed all of the rules, etc., I still felt distant from God. I believed that God was a God of mercy and grace and I believed that He loved us. I believed all of these things, but I never believed them for myself.

I was caught up in rules. If I was struggling with something, I never remembered the truth of grace for myself. I would immediately tear myself down and realize that I needed to work to “make it up to God.” I was so deceived. I told myself that God was grace and love, and yet, in my mind, I couldn’t accept the grace and love God was pouring out to me until I was maybe slightly “worthy.” I couldn’t accept what Christ gave His LIFE for until I had worked to earn it.

Looking back, it still haunts me how deceived I was. I was a 15-year-old girl who was working to follow a set of “rules”. I was a 15-year-old girl who was trying to work toward the impossible. Some days I felt like a “good person”. A “good Christian”. I felt put together. Other days, I felt so alone. So undeserving. I felt as though I was in the middle of a constant, uphill battle that would never cease.

One day, at 16, it all changed.

I had the most real encounter with my Savior and I can say with complete certainty that it changed my life forever.

I truly saw Jesus for the first time.

I quickly learned that once you truly see Jesus, you cannot help but fall in love. I finally was able to break free from the chains holding me back from a pure joy that made me feel whole. Once I really saw Jesus, I felt His love for me. I was no longer a slave to the rules and I was no longer a slave to all of the expectations I put on myself. Most importantly, I was no longer a slave to the lies that had kept me captive for so long.

Judah Smith, a pastor at The City Church in Seattle, WA, (and one of my all time favorite pastors and authors) said something that truly impacted me:

“I think if Jesus had one shot at fixing us, He’d tell us how much He loves us. Jesus loves us right now, just as we are. He isn’t standing aloof, yelling at us to climb out of our pits and clean ourselves up so we can be worthy of Him. He is wading waist-deep into the muck of life, weeping with the broken, rescuing the lost, and healing the sick.”

Jesus didn’t sacrifice His life for you and me just so that we could feel hindered and alone in our attempts to work to become “right with God.” Jesus wasn’t tortured and hung on the cross so that I would feel as though I would finally be truly loved, forgiven, and cherished once I had my life together.

That’s just not how it works.

Once I truly entered the presence of Jesus, one thing became clear: I am loved as I am.

I had the order all wrong. We don’t somehow earn our salvation by living a sin-free life full of good works and then get to experience Jesus and all that He has to offer.

Jesus was reaching out to me in my darkest times, loving me in the midst of the pit I was in. He meets us exactly where we are. Instead of scorning us and looking down on us, He wants to pick us up off of our feet, scrape off the dirt, and carry us in His loving arms. He wants us to walk with Him out of the deep pit that we found ourselves in.

And that’s not the end of it.

He wants us to continue walking straight out of the darkness, and He wants us to grow closer to Him.

Judah Smith says it perfectly in his book “Jesus Is __”:

“Get to know Him yourself, and let the goodness of God change you from the inside out.”

We don’t transform ourselves so that we may experience the love of God. We experience the love of God first and that same love transforms us.

The day I saw Jesus, I fell in love. The lies that had held me down shattered like glass, and I started a true relationship with Jesus and saw quickly how He was transforming my heart.

Every day I get to walk with God, and I know that He will never forsake me. Every day I am reminded of the truth and the lies of working for salvation will never have power over me again.

The day I saw Jesus, I experienced a love like no other.

To read more from Julie, you can follow her blog here.

I’d like to introduce my wife Kristen Huff as the guest writer for this post. I am thrilled she has taken the opportunity to respond to Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman which released earlier this summer.

Disclaimer: Spoiler Alert

Everyo ne has that person in their life. You know, the one you look up to. The one who can do no wrong. The one you trust that if all the world goes crazy, he or she will be right there, a consistent moral force to speak truth into your life.

ne has that person in their life. You know, the one you look up to. The one who can do no wrong. The one you trust that if all the world goes crazy, he or she will be right there, a consistent moral force to speak truth into your life.

For Scout Finch that person was always her dad, Atticus. He had always been the one to do what was right. He was the rock she and her brother depended on, as well as the one who did what no one else in the town had the guts to do. We all remember the trial in To Kill a Mockingbird. He boldly defended a negro in court at a time when race relations were at the height of social issues.

In Go Set a Watchman, a grown-up Scout finds herself once again observing her father amidst a heated discussion concerning race relations. Yet, she is mortified to see that, instead of being the bold defender of negroes, her dad, and also her fiancé, quietly sit, blending in with the crowd.

She runs from the scene carrying a storm of emotions. What follows is a bout of physical and emotional illness as she tries to grasp the fact that her father has somehow changed, or perhaps was never the man she thought he was. After several attempts to distract herself from the betrayal she feels by those closest to her, she runs to her uncle for answers. His explanation for her devastation is incredibly enlightening:

“Every man’s island, Jean Louise, every man’s watchman, is his conscience. There is no such thing as a collective conscious. […] now you, Miss, born with your own conscience, somewhere along the line fastened it like a barnacle onto your father’s. As you grew up, when you were grown, totally unknown to yourself, you confused your father with God. You never saw him as a man with a man’s heart, and a man’s failings — I’ll grant you it may have been hard to see, he makes so few mistakes, but he makes ’em like all of us. You were an emotional cripple, leaning on him, getting the answers from him, assuming that your answers would always be his answers.”

I had to stop after this and think. I have been thinking about this scene for several days now, especially in light of recent events at my alma mater, North Greenville University. Do we not often place unrealistic expectations on our leaders, heroes, and parents? We set them up in our minds as these perfect people who, if they sin at all, it is just a small fib or a sharp word here or there. To find out that a moral leader or hero has done something horrible feels like the end of the world to us. Like Scout, we go screaming for answers and assume our entire faith has been shattered.

Let’s do some self-examination for a moment. How many of us really made it through college without some sort of sexual sin? I think, if we are honest, that would be no one. So, there we all are, 18 years old and thinking we are spiritual. Attending chapel, taking part in ministry and secretly making out with our significant other and probably doing a whole lot more than that. I have a feeling our professors/faculty/administrators and, dare I even say, our president had a pretty good idea about our “secret sins,” but did they broadcast it and condemn us for it? No. They just kept on serving us, loving us, and praying for us. Eventually, the Holy Spirit got through, and those of us who were truly saved repented, beginning the process of making things right.

So, here is my conclusion after several days of thinking through this book in light of recent events. We all have a watchman, our conscience, and if we are saved, it is controlled by the Holy Spirit. The best thing to do is what it says in Psalm 130:3-8:

If you, Lord, kept a record of sins,

Lord, who could stand?

But with you there is forgiveness,

so that we can, with reverence, serve you.

I wait for the Lord, my whole being waits,

and in his word I put my hope.

I wait for the Lord

more than watchmen wait for the morning,

more than watchmen wait for the morning.

Israel, put your hope in the Lord,

for with the Lord is unfailing love

and with him is full redemption.

He himself will redeem Israel

from all their sins.

In the tail end of Ephesians 4, Paul shifts his thoughts from what are, as my dad calls them, the redwoods of theology and doctrine that constitute Ephesians 1-3 (you know, the veritable grab bag of predestination, depravity, progressive sanctification, and a side of nachos) toward the stuff of practical living. He begins in 4:25 with the exhortation to “put away falsehood” and to “not let the sun go down on your anger,” clear encouragement that is forthright and incisive.

But what seems to be fairly easy-going in the first few pieces – speak the truth, be angry and do not sin – becomes quite complicated as the list continues. By the end, we are told only to speak what is good for building up and to let all bitterness, wrath, anger, clamor, slander, and malice be put away from us. Sheesh. It’s safe to say this collection of living wisdom requires the work of the Holy Spirit in us to bring it about, a truth which is more than likely Paul’s entire point.

Yet, as we rely on the Spirit of the Living God to be at work in us (Phil. 2:13), we are not given the allowance to drift slowly to sleep as Paul’s list reveals itself. Though it is God at work in us, we are still commanded to put our whole being to the task of sanctification with “fear and trembling” (Phil. 2:12).

With this sort of focus and examination in mind, I’d like to hone in on one of Paul’s commands in particular:

“Let the thief no longer steal, but rather let him labor, doing honest work with his own hands, so that he may have something to share with anyone in need.” -Eph. 4:28

Though there is much to be gleaned from this verse on the virtue of work, the value of sharing, and the necessity of compassion in capitalism (for a separate post, I’m sure), I’d like to offer three observations regarding theft in the life of a Christian.

#1 – Taking what isn’t yours and not taking what is yours are both sins.

While the knee-jerk reading of this verse tends to lean toward a “Thou-shalt-not-steal” cautioning, we must not neglect the possibility of a more ubiquitous form of theft: robbing oneself. It is true that we must not steal what is not ours, but it is also true that we must not steal what has been freely given us by not allowing ourselves to enjoy it. This form of theft is quite familiar to many of us. How often have we refused the gift of forgiveness Christ offers? How many of us live under the condemnation and guilt of gracelessness when the grace of Christ has been extended to us? How many of us decline the gift the Giver has lavished on us in the name of self-reliance? For too many of us, we admit Christ broke the chains that bound us but rather than leave them at the foot of the cross, we pick them up and flagellate away. The chasm between penance and penitence is vast.

We must believe God when He says, “I give you grace, forgiveness, justification, joy.” To say no to these is to say no to Christ. We steal from ourselves when we acknowledge Christ with our mouths but decline the gift of salvation, the whole gift with all its bells and whistles.

#2 – Thieves steal more than treasure.

Stealing a car is bad. Stealing money from your neighbor is bad. Stealing time your children deserve is…well…

Though many American Christians balk at the notion they must be told not to steal (“Please, I wear a tie to work. I’m no thief.”), far too many of us steal regularly when it comes to the passing of our time. When Paul tells us we must no longer steal, we ought to look at the time we steal from our spouse by overcommitting to hobbies, time we steal from our children by lying on the couch, time we steal from our pastor by staying home. It would seem we do not need ski masks to be thieves.

#3 – Taking what must not be taken and not giving what must be given are both sins.

Similar to observation #1, this truth tends to glisten when you tilt the verse at an angle. Paul ends his verse with the overall purpose of the command: “…so that he may have something to share with anyone in need.” Paul gives us the why. We must no longer steal but work heartily so that we may have something to share with anyone in need. This means that it is not enough to simply stop stealing and start earning. Hoarding is theft. When we fill our own barrels for the sake of grinning at their fullness, we rob those in need of what God has called us to share. As the sage once said, humans have two hands and one mouth. We ought to contribute twice as much as we consume.

Most importantly, we must remember that “honest work and just reward” (to quote Javert) existed pre-Fall, thus they are a design feature built in to God’s original plan for mankind. Adam was employed in the garden before he was evicted from the garden (Gen. 2:15). We must enjoy our work as a part of God’s design which means we must both give of our plenty and receive of God’s plenty with the widest of smiles.