A poem to my students…

I wonder if it’s a sonnet,

The poem of your life,

As I hear your shoes squeak their stanzas across the floor to your desk

And you click your blue mechanical pencil

Twice to take a quiz.

For I happened to notice two index cards,

Like a light pink couplet,

Tucked beneath the tidy layers of your notebook

As you closed your eyes, breathed, reassured yourself

Of what you knew and filled your name at the top.

Or do you live and breathe in music,

All elbows and gym bags, your fingers

Twitching steadily the edges of your sweatshirt?

Perhaps your life is a lyric, a rhythm

Kept in meter by the beat of basketballs,

Or the wild and fearless drummings of your

Feet along the track?

Or you, there in the far row,

Do you see the world in free verse?

Eyes bright from gazing through kaleidoscopes,

Bending the sky around your ballpoint pen?

From here I see your frenzied scribbling in that beat-up journal,

The back of your homework, the length of your arm,

Scrambling to seize your swelling thoughts,

Your echoing afterthoughts,

Your madcap fever of creativity.

And I bet hers is a ballad, a song,

Her eyes telling the fear in the horizons,

Dreaming of afternoon, of evening,

Of the time she’ll spend with her father

Before his illness takes a turn.

Whatever they are,

These poems in your mouths, your hands, your smiles,

They somehow fit each one of you, like shadows

Filled with beauty and, ironically,

With light.

And when I am old,

Beyond the reach of my podium,

My pen, my worn and dog-eared Hamlet,

I will see you all,

Again and again and again,

As young as autumn leaves

Reddening, then leaping

Into the constant winds of change.

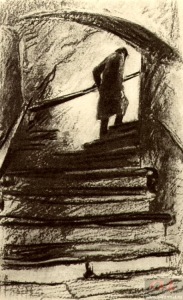

I am working my way through Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment and was struck by one of its early scenes depicting a drunkard in a St. Petersburg tavern bemoaning his vices, as well as the costs they have accumulated, to the novel’s protagonist Rodya Raskolnikov.

I am working my way through Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment and was struck by one of its early scenes depicting a drunkard in a St. Petersburg tavern bemoaning his vices, as well as the costs they have accumulated, to the novel’s protagonist Rodya Raskolnikov. As an English teacher, I often instruct my students to discuss the characters and actions in whatever work we are studying by using the present tense. For instance, Hamlet contemplates death as he faces Yorick’s empty skull, Beowulf aspires toward a sense of eternal glory as he wrenches Grendel’s arm off, and Gatsby stretches ever farther for that ephemeral green light on Daisy’s dock. I remind them that the literary present tense preserves the immediacy and continuous action of the narrative upon each individual reading; these characters, in a sense, are always contemplating, aspiring, stretching every time we open the book.

As an English teacher, I often instruct my students to discuss the characters and actions in whatever work we are studying by using the present tense. For instance, Hamlet contemplates death as he faces Yorick’s empty skull, Beowulf aspires toward a sense of eternal glory as he wrenches Grendel’s arm off, and Gatsby stretches ever farther for that ephemeral green light on Daisy’s dock. I remind them that the literary present tense preserves the immediacy and continuous action of the narrative upon each individual reading; these characters, in a sense, are always contemplating, aspiring, stretching every time we open the book.