As I am working to lift Eden.Babel onto its feet, one of my primary concerns and interests is in the field of wordsmithing. Excellent craftsmanship is a noble goal, no matter what the smithy of your particular ilk is filled with; the mason may use bricks, the painter his brushes, the musician his notes. The writer uses words. Since the usage of words is a staple of most people’s daily living, the writer has a peculiarly interesting challenge before him. Not everyone uses paint or notes or bricks in the course of their 24 hours, but we almost all use words. Some may wish others used fewer, but that’s another post. Writers are tasked to take a seemingly mundane feature of our existence (words and their arrangement) and spin them in such a way that they can knock a hearer off his or her feet. As Mary, Queen of Scots once said of John Knox, “I fear his tongue and pen more than the armies of England.”

As I have immersed myself over the years in the world of literature, poetry, and many other forms of the written word as well as committed myself to the weaving of my own words, I have decided to consider five of the most influential writers in my own life. This list, as with most lists of its kind, is written in the current moment, meaning I am quite available to be moved and impacted by other writers than these five in the future just as I certainly have been in the past. Also, this list does not factor in God and His Word, the most influential book ever written. As a Christian, I heartily affirm the influence of the Word of God to be a given.

5. C.S. Lewis

This choice really stems from how much of Lewis I have read over the past ten or so years. As a child, I was raised on the Narnia stories and have just recently started to go back through them. I was likewise raised on the BBC films of the Narnia books (you know, the Lucy with her wonderful teeth, the giant beavers, the animatronic Aslan. Classics…). As I moved into college, I began to wade through more of Lewis’ work, including The Great Divorce, Till We Have Faces, The Screwtape Letters, and others. During a bleaker period, I picked up A Grief Observed, which was very helpful. Finally, while studying literature in grad school, I took a course on Lewis and Tolkien in London. There, I dove headlong into his space trilogy, The Four Loves, The Weight of Glory, and a great deal of his biography. Since then, I’ve read Surprised by Joy, a number of his poems, and continue to read him more and more. His commitment to both logic and fancy is contagious, and I look to him for an abundance of insight and imagination.

Recommended reading: Out of the Silent Planet, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, The Screwtape Letters, “The Future of Forestry”, “Meditation in a Toolshed”

4. Billy Collins

In compiling this list, I made an effort to select writers that represent different genres and approaches. With this in mind, Collins is certainly my poetic choice. He served as poet laureate for the U.S. in the early 2000s, and I even had the privilege of meeting him at a poetry reading in Nashville. Collins’ poetry is known for its accessibility, humor, and seeming simplicity. For this, he may certainly be termed a poet of the people. Yet, his writing is elusive, deep, biting, startling, and some of the most moving verse I’ve encountered. Collins has the unique ability to take a simple reality (weighing a dog, weaving a lanyard at camp, studying geography) and transform it into a transcendent experience as he observes the fullness of feeling, sensitivity, and power that can exist in any given human moment. He treats love, loss, friendship, fear, and longing as though they are old pals, conversing freely with them over coffee at midnight. He laughs through awkwardness and shudders at morning light. He can turn any event on its head at the start of a single stanza and leave you breathless upon completing it. I cannot speak highly enough of his work, and I have thoroughly enjoyed making my way through his collections.

Recommended reading: “The Lanyard”, “Weighing the Dog”, “Introduction to Poetry”, “Plight of the Troubadour”

3. Ben Gibbard

Though he is primarily regarded as a musician, Gibbard’s lyric writing ranks right up there with the best of them. He is the frontman for the indie rock band Death Cab for Cutie and has become a respected voice for poetic melancholy in our generation. I caught on to Ben Gibbard’s beautiful writing when I was first introduced to DCFC’s album Transatlanticism by my little brother, Chris. I remember being immediately struck by the quality of their music and Gibbard’s soaring melodies, so I decided to go through the whole album several times over on my own. What I discovered as I walked alongside his verses and choruses, acutely attuned to the narratives he was singing, was simply breathtaking. I was speechless. Gibbard could weave a lyrical phrase unlike anyone I had ever heard, and what had ignited a glimmering flame of attraction and sympathy for him in Transatlanticism was fueled to a wildfire in Plans, their 2005 album. By this time, I had begun playing music myself with a friend of mine and had become interested in lyric writing as a form of expression not dissimilar from poetry. As I delved further into writing music and writing lyrics, Gibbard always served as the standard, the pitch in which all of my own writing was set. To this day, I look to Ben Gibbard’s poetic sensibility, astounding mastery of metaphorical language, and sobering emotional melancholy for a bracing dose of creative power to shock me back into my own love and passion for writing.

Recommended reading/listening: “What Sarah Said”, “Brothers on a Hotel Bed”, “Little Wanderer”, “Transatlanticism”, “We Looked Like Giants”, “Title and Registration”, “Summer Skin”, “No Room in Frame”

2. F. Scott Fitzgerald

If you are reading this and you are a former/current student of mine, you saw this coming; I tend to reference Fitzgerald all the time in class. Simply put, there will never be another F. Scott Fitzgerald. I dedicated my master’s thesis to the life and work of this marvelous author, so I am quite biased. I do believe, however, that his prophetic understanding of American narcissism, the nature of sin, the transience of happiness, and the ache of unrequited love have cemented him in literary history as a true icon of the highest caliber. He was painfully romantic, given over at once to both the beauty and the hopelessness of his dreams. He desired a greatness that would always be two steps ahead of him, doubting his ability to reach it yet straining forward all his life. He was exuberantly happy and painfully miserable. He rose meteorically and fell disastrously. He fought with God and embraced God. He could dash off a crowd-pleaser in a matter of hours (often hungover) and labor meticulously over a failing novel for years. And his writing is simply magnificent. Every page of his work is filled with both diamonds and dust, champagne and charlatans. He wrote like Mozart, lyrically effusing phrases and sentences that seemed like they had been written ages ago as he simply pulled them out of the air and blotted them on paper. He wrote like most men breathe, pouring forth what was already in there, effortlessly. Much of my love for the imaginative wonder and hope in life is credited to his work. I will read him until I can no longer read.

Recommended reading: The Great Gatsby, This Side of Paradise, “‘The Sensible Thing'”, “Thank You for the Light”, “The Cut-Glass Bowl”, “The Jelly-Bean”

1. Doug Wilson

Doug Wilson is a theologian, pastor, and highly prolific writer with dozens of books to his name. If there is any writer who has helped shape my thinking, provoke my curiosity, satisfy my imaginative scope, push my pursuit of excellence, hone my understanding of joy, and confirm my desire for the full, abundant, passionate life in Christ, Doug Wilson is that writer. His work ranges greatly, covering such topics as culture, theology, rhetoric, argument, marriage, childrearing, father hunger, eschatology, apologetics, creative writing, Beowulf, wisdom, the Middle Ages, hearty laughter, Calvinism, gratitude, poetry, robust singing, and much more. His writing has led me deeper into the conviction that God is God and God is good. I am so deeply indebted to his writing and his teachings on the Christian life that to remove his influence from my life would be to remove a great deal of who I have become in my faith in Jesus. While the content of his work is overwhelmingly edifying and helpful, his style is simply inimitable. He wields the English language like a battle axe, sharp at the edge and effective in every blow. He is clever, witty, incisive, kind, colorful, lyrical, and quotable. He is memorable, humorous, startling, paradoxical, and charming. He is jolly and forthright. He is happy and rigid. In a word, he is full. My admiration and respect for Wilson’s writing cannot be expressed enough, and I could speak at greater and greater lengths in praise of his command over the written word.

Recommended reading: Heaven Misplaced, Angels in the Architecture, Rules for Reformers, Joy at the End of the Tether, Wordsmithy, God Is

In Ephesians 2, Paul declares that we as Christians are the “workmanship of God”:

In Ephesians 2, Paul declares that we as Christians are the “workmanship of God”:

It is true that we are all characters in the great Story of God, called to our own journeys as we navigate the treacherous waters of a perilous world. It is also true that the dividing line between our actions in these journeys can be as thick as lead, the difference between noble Reepicheep, sailing into the majesty of Aslan’s country, and the self-absorbed Eustace, inching steadily toward the dragon’s den. Some are brave, some are weak.

It is true that we are all characters in the great Story of God, called to our own journeys as we navigate the treacherous waters of a perilous world. It is also true that the dividing line between our actions in these journeys can be as thick as lead, the difference between noble Reepicheep, sailing into the majesty of Aslan’s country, and the self-absorbed Eustace, inching steadily toward the dragon’s den. Some are brave, some are weak.

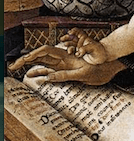

A few weeks ago, I had the privilege of touring the Museum of Biblical Art in Dallas and discovered a beautiful painting by Botticelli titled Madonna of the Book. In the center of this piece sits Mary with the Christ child on her lap as they both read from a medieval book of hours, a sacred devotional text common to Botticelli’s generation. Noticeably, Mary is pensive, contemplative, and even mournful in her pose as she studies the book.

A few weeks ago, I had the privilege of touring the Museum of Biblical Art in Dallas and discovered a beautiful painting by Botticelli titled Madonna of the Book. In the center of this piece sits Mary with the Christ child on her lap as they both read from a medieval book of hours, a sacred devotional text common to Botticelli’s generation. Noticeably, Mary is pensive, contemplative, and even mournful in her pose as she studies the book. He was born to die. This is the will of God that “Jesus, delivered up according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God, [be] crucified and killed by the hands of lawless men” (Acts 2:23). Indeed, Christ came into this world to “give his life as a ransom for many” (Matt. 20:28). As Mark Lowry famously wrote in a

He was born to die. This is the will of God that “Jesus, delivered up according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God, [be] crucified and killed by the hands of lawless men” (Acts 2:23). Indeed, Christ came into this world to “give his life as a ransom for many” (Matt. 20:28). As Mark Lowry famously wrote in a  Yet, Christ guides her hand with His. “Keep reading. Keep reading.” Notice His left hand holding hers and His right hand guiding her back to the story. We must keep reading. Christ must die on the cross so that we must not. His steady and victorious look to His mother tells us everything. “I must do this for you,” he says to her and to us. “I love you. You must keep reading.” For as we keep reading, we discover that the story does not end at His death. In the words of the Battle Hymn, “Let the hero, born of woman, crush the serpent with His heel […] His truth is marching on.” He marches on. He marches on. Glory, glory, hallelujah.

Yet, Christ guides her hand with His. “Keep reading. Keep reading.” Notice His left hand holding hers and His right hand guiding her back to the story. We must keep reading. Christ must die on the cross so that we must not. His steady and victorious look to His mother tells us everything. “I must do this for you,” he says to her and to us. “I love you. You must keep reading.” For as we keep reading, we discover that the story does not end at His death. In the words of the Battle Hymn, “Let the hero, born of woman, crush the serpent with His heel […] His truth is marching on.” He marches on. He marches on. Glory, glory, hallelujah.

If we are all actors in the cosmic theater of life, then the notion nobody is watching must be the most harrowing of all. Our tragedies and our triumphs would ultimately amount only to the enlargement or diminishment of the boulders that we, like Sisyphus, simply push up the mountainside. Unfortunately, the best the atheist can tell us in response to this horrendous thought is that we must imagine Sisyphus to be happy.

If we are all actors in the cosmic theater of life, then the notion nobody is watching must be the most harrowing of all. Our tragedies and our triumphs would ultimately amount only to the enlargement or diminishment of the boulders that we, like Sisyphus, simply push up the mountainside. Unfortunately, the best the atheist can tell us in response to this horrendous thought is that we must imagine Sisyphus to be happy.

They were made for something. Yet, in this opening scene, we see each of them longing to be used, to be needed, to be fulfilled, with no “master” there to answer their quiet pleas for meaning and purpose.

They were made for something. Yet, in this opening scene, we see each of them longing to be used, to be needed, to be fulfilled, with no “master” there to answer their quiet pleas for meaning and purpose.

One of the most striking elements of the opening scene is the strict routine our characters keep in maintaining the cottage for their master. Even though it has been, as Kirby the Vacuum puts it “2,000 days” since the master has been there, they work diligently to serve their purpose to a deserted audience. Kirby relentlessly cleans every speck of dirt on the floor, Radio entertains an empty room, and Toaster toasts…nothing. This is the despair of absurdity, the grief of discovering that in the great play of life, there may be no one watching. As Macbeth famously declares:

One of the most striking elements of the opening scene is the strict routine our characters keep in maintaining the cottage for their master. Even though it has been, as Kirby the Vacuum puts it “2,000 days” since the master has been there, they work diligently to serve their purpose to a deserted audience. Kirby relentlessly cleans every speck of dirt on the floor, Radio entertains an empty room, and Toaster toasts…nothing. This is the despair of absurdity, the grief of discovering that in the great play of life, there may be no one watching. As Macbeth famously declares: Interestingly, we get a quick image of such a “walking shadow” as Radio plays “Tutti Frutti” to begin the cleaning chores, which, ironically, are meaningless without the master at home.

Interestingly, we get a quick image of such a “walking shadow” as Radio plays “Tutti Frutti” to begin the cleaning chores, which, ironically, are meaningless without the master at home. “A CAR!” they yell, filled with the hope of purpose. At last, our master is home! They scramble around the cottage for anything they can find to reach the attic window, their best chance to catch a glimpse of the master’s homecoming. They work together, reaching up to heaven to see the master.

“A CAR!” they yell, filled with the hope of purpose. At last, our master is home! They scramble around the cottage for anything they can find to reach the attic window, their best chance to catch a glimpse of the master’s homecoming. They work together, reaching up to heaven to see the master. The master bursts through the door in full and shining glory, arms out to welcome his weary and wistful friends, “Home, Sweet Home” lovingly pinned to the wall. What a picture of God and the beauty of the great Homecoming. The glorious moment of being reunited with our Master, our longing for purpose fulfilled, our existences meaningful once more.

The master bursts through the door in full and shining glory, arms out to welcome his weary and wistful friends, “Home, Sweet Home” lovingly pinned to the wall. What a picture of God and the beauty of the great Homecoming. The glorious moment of being reunited with our Master, our longing for purpose fulfilled, our existences meaningful once more.