Toward the end of Prince Caspian, after the decisive battle for the Narnian throne against the usurper Miraz, Aslan relays to Caspian the story of his heritage to explain his rightful place as the true king of Narnia. His tale, however, is not filled with accounts of glorious kings and queens or daring adventures on the high seas (though Caspian will see plenty on the Dawn Treader). Rather, Aslan recounts stories of thieves, murderers, drunkards, pirates, quarrelers, and fierce tyrants. As Aslan describes this history, the young man’s face sinks into a deep sadness:

Toward the end of Prince Caspian, after the decisive battle for the Narnian throne against the usurper Miraz, Aslan relays to Caspian the story of his heritage to explain his rightful place as the true king of Narnia. His tale, however, is not filled with accounts of glorious kings and queens or daring adventures on the high seas (though Caspian will see plenty on the Dawn Treader). Rather, Aslan recounts stories of thieves, murderers, drunkards, pirates, quarrelers, and fierce tyrants. As Aslan describes this history, the young man’s face sinks into a deep sadness:

“Do you mark all this well, King Caspian?”

“I do indeed, Sir,” said Caspian. “I was wishing that I came of a more honourable lineage.”

What follows from Aslan is perhaps one of the most striking and insightful passages from the whole of the Narnia series:

“You come of the Lord Adam and the Lady Eve,” said Aslan. “And that is both honour enough to erect the head of the poorest beggar, and shame enough to bow the shoulders of the greatest emperor on earth. Be content.”

This keen and penetrating truth strikes at the heart of young Caspian, instantly quieting him (the next sentence simply states, “Caspian bowed.”). And, if we are reading correctly, it instantly quiets us. One can almost feel the warm, yet powerful breath of the Lion as he commands us to “be content.”

It is true that humanity is characterized by both the responsibility and privilege of bearing the very image of God. We are unordinary. Yet, in this account, we encounter the unbelievably weighty tension between being the jewel of God’s creation and being depraved sons of disobedience. We are both diamonds and dust. Being human is an honor and a shame.

How many of us, like Caspian, look around at our humanity and mourn our tattered lineage? How many videos of tiny fingers and legs in petri dishes can we stomach before we shake our heads in despair at what it has come to mean (or not mean) to be human?

But there, right there, Aslan instructs us to “be content.” In our vacillation between pride and despair, honor and shame in the human race, we must remember to be content. The Lord is sovereign. The Lord is King. Blessed be the name of the Lord.

Or, as Lewis would say, “Aslan is on the move.” Remember how The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe concludes: the winter is thawing and it promises to be a real spring. Or, as Tolkien would have it, everything sad is coming untrue.

So while we face dark days in our humanity, ruefully wishing our story were more noble, we must bow our heads like Caspian and be content, not in our strength to withstand the coming evils but in the power and certainty of Christ’s victory over all things. Aslan assures Caspian because he has the authority to do so. May we learn to trust the King of kings in our honorable and our shameful days, for He alone will make all things new.

It is true that we are all characters in the great Story of God, called to our own journeys as we navigate the treacherous waters of a perilous world. It is also true that the dividing line between our actions in these journeys can be as thick as lead, the difference between noble Reepicheep, sailing into the majesty of Aslan’s country, and the self-absorbed Eustace, inching steadily toward the dragon’s den. Some are brave, some are weak.

It is true that we are all characters in the great Story of God, called to our own journeys as we navigate the treacherous waters of a perilous world. It is also true that the dividing line between our actions in these journeys can be as thick as lead, the difference between noble Reepicheep, sailing into the majesty of Aslan’s country, and the self-absorbed Eustace, inching steadily toward the dragon’s den. Some are brave, some are weak.

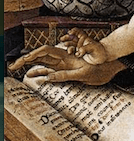

A few weeks ago, I had the privilege of touring the Museum of Biblical Art in Dallas and discovered a beautiful painting by Botticelli titled Madonna of the Book. In the center of this piece sits Mary with the Christ child on her lap as they both read from a medieval book of hours, a sacred devotional text common to Botticelli’s generation. Noticeably, Mary is pensive, contemplative, and even mournful in her pose as she studies the book.

A few weeks ago, I had the privilege of touring the Museum of Biblical Art in Dallas and discovered a beautiful painting by Botticelli titled Madonna of the Book. In the center of this piece sits Mary with the Christ child on her lap as they both read from a medieval book of hours, a sacred devotional text common to Botticelli’s generation. Noticeably, Mary is pensive, contemplative, and even mournful in her pose as she studies the book. He was born to die. This is the will of God that “Jesus, delivered up according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God, [be] crucified and killed by the hands of lawless men” (Acts 2:23). Indeed, Christ came into this world to “give his life as a ransom for many” (Matt. 20:28). As Mark Lowry famously wrote in a

He was born to die. This is the will of God that “Jesus, delivered up according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God, [be] crucified and killed by the hands of lawless men” (Acts 2:23). Indeed, Christ came into this world to “give his life as a ransom for many” (Matt. 20:28). As Mark Lowry famously wrote in a  Yet, Christ guides her hand with His. “Keep reading. Keep reading.” Notice His left hand holding hers and His right hand guiding her back to the story. We must keep reading. Christ must die on the cross so that we must not. His steady and victorious look to His mother tells us everything. “I must do this for you,” he says to her and to us. “I love you. You must keep reading.” For as we keep reading, we discover that the story does not end at His death. In the words of the Battle Hymn, “Let the hero, born of woman, crush the serpent with His heel […] His truth is marching on.” He marches on. He marches on. Glory, glory, hallelujah.

Yet, Christ guides her hand with His. “Keep reading. Keep reading.” Notice His left hand holding hers and His right hand guiding her back to the story. We must keep reading. Christ must die on the cross so that we must not. His steady and victorious look to His mother tells us everything. “I must do this for you,” he says to her and to us. “I love you. You must keep reading.” For as we keep reading, we discover that the story does not end at His death. In the words of the Battle Hymn, “Let the hero, born of woman, crush the serpent with His heel […] His truth is marching on.” He marches on. He marches on. Glory, glory, hallelujah.

If we are all actors in the cosmic theater of life, then the notion nobody is watching must be the most harrowing of all. Our tragedies and our triumphs would ultimately amount only to the enlargement or diminishment of the boulders that we, like Sisyphus, simply push up the mountainside. Unfortunately, the best the atheist can tell us in response to this horrendous thought is that we must imagine Sisyphus to be happy.

If we are all actors in the cosmic theater of life, then the notion nobody is watching must be the most harrowing of all. Our tragedies and our triumphs would ultimately amount only to the enlargement or diminishment of the boulders that we, like Sisyphus, simply push up the mountainside. Unfortunately, the best the atheist can tell us in response to this horrendous thought is that we must imagine Sisyphus to be happy.